Hi! I’m Hannah James, journalist, writer and editor, and this is where I review nature books, and think about nature-related topics out loud. Thanks for reading!

What I’m reading

Taiwan is an unstable country: unstable both literally (it experiences more than 2000 earthquakes every year) and politically (China regards it as a breakaway province, but its democratically elected leaders say it is a sovereign state).

It’s a country Jessica J. Lee, author and academic, has a shifting, uncertain relationship with: her maternal grandparents moved from rural China to Taiwan after the Second World War, following the Chinese government’s shift to the island. They had a child - Lee’s mother - then emigrated to Canada, where Lee’s mother met Lee’s father, whose parents were Welsh. Lee has never lived in Taiwan, but moved as an adult to the UK, then to Germany.

Photo by Lisanto 李奕良 at Unsplash

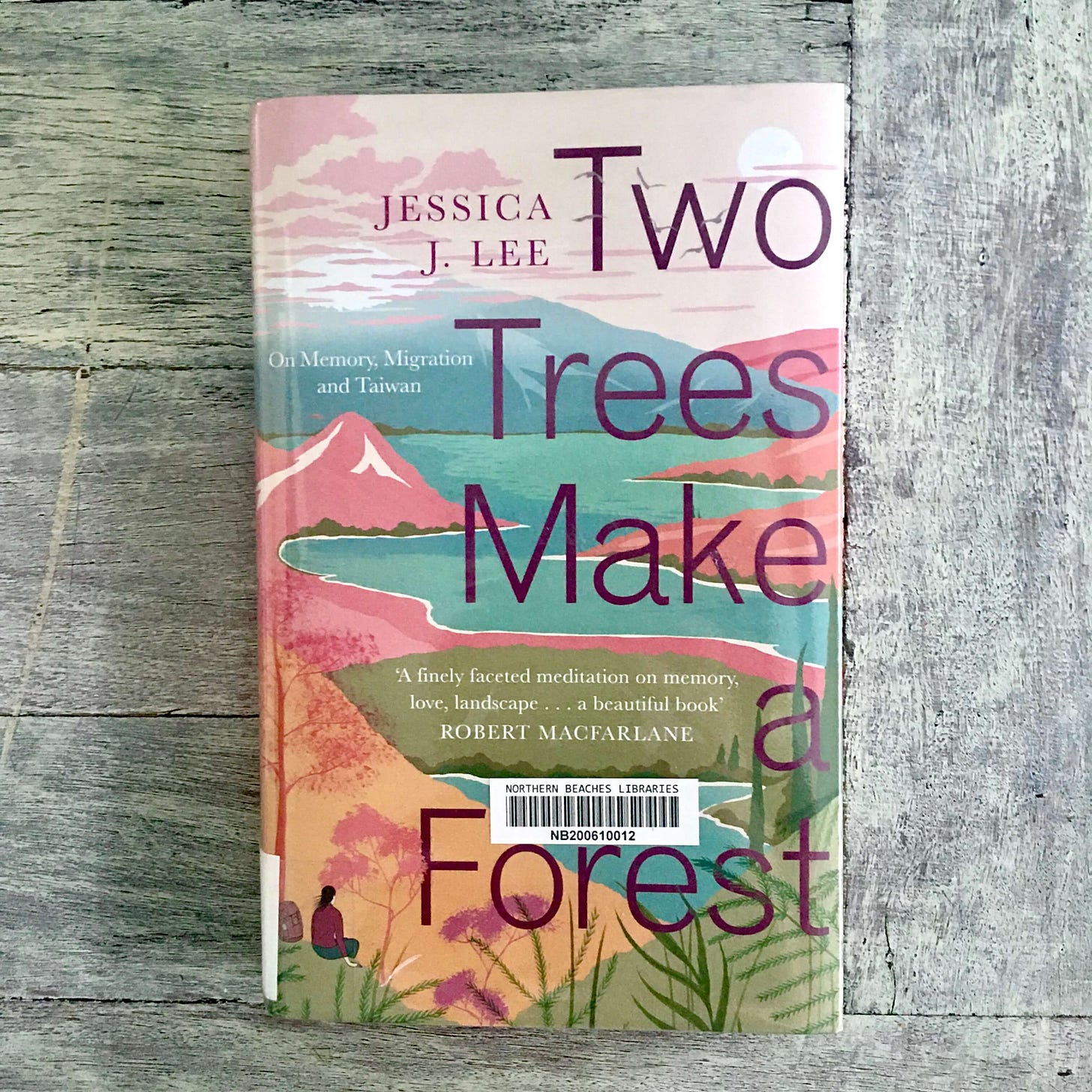

Amid all these migrations, something in her reaches out towards Taiwan. “This is a story of that island. And it is also a story of family,” she writes in Two Trees Make A Forest: On Memory, Migration and Taiwan. Of that family’s complicatedly international story, she writes:

“Our histories stretched across places imprecisely, until our borders grew too hazy to define.”

All stories about countries - not to mention all stories about families - are stories about identity, and this one is no different.

“My mother, sister and I stumbled over whether to call ourselves Chinese - we weren’t from a China that exists any longer - or Taiwanese. No single word can contain the movements that carried our story across waters, across continents.”

“I negotiated the world as a dual citizen of Britain and Canada, casting my life in those frames of reference. The question of whether to call myself Taiwanese or Chinese felt a complication too far. I often found myself with too many names, too many homes, and no fixed sense of order to arrange them in. A use of just one was an erasure of another.”

Lee is an environmental historian, as well as the author of a previous work of nature writing/memoir, Turning: A Swimming Memoir, and so, as she settles in Taiwan for a three-month stay to write, to hike and to investigate her family history, she naturally weaves into her work the landscape history of the place she is getting to know.

“I moved from the human timescale of my family’s story through green and unfurling dendrological time, to that which far exceeds the scope of my understanding: the deep and fathomless span of geological time.”

Photo by Ruslan Bardash on Unsplash

Along with the history of Taiwan, she discovers her grandfather’s story, a air force pilot whose sharp mind was lost to Alzheimer’s, and begins to unravel why her grandparents were so determinedly silent about the families they left behind.

Some of Lee’s nature writing is lovely:

“A green washes itself over Taiwan’s hills, a mottled, deep hue that reminds me more of lake than land, of darkened water-weed more than tree. The green rolls out on the horizon, glinting with occasional light, but more often steaming with the low-hanging clouds that cling to the border between hillside and sky. That verdant hue is unlike any I know.”

And her ideas about the ways nature and culture intersect are intriguing:

“I think often that it is in plants that Taiwan’s recent history can readily be seen… Plants come to represent us on city streets, in parks, in our poetry, and shared dreams. Nature unfolds amongst us, shaped by our commitments - whether scientific, cultural, or political.”

She braids together Taiwan’s geological mutability, its mountains that shake and slide from the volcanic forces at work beneath them, with the shifting sands of her own identity:

“A taxi driver asked me why my Mandarin was so good for a foreigner. ‘My mother is from Taiwan,’ I explained, and he turned on me in reprimand. ‘Then why is your Mandarin so poor?’”

Many of her observations about being a perpetual expat are astute (“We who make our homes elsewhere give ourselves away in the little things we can’t quite control”) and I deeply understand her quest to physically walk her way into knowledge of and identification with her quasi-ancestral home. But this book proves how difficult it is to weave all these strands - memoir, nature writing and history - into one cohesive and beautiful whole. I hesitate to criticise because so much about this book is lovely, but certainly the pacing is uneven in places, and the transitions between different storylines are jerky at times. Mostly, however, Lee succeeds in her ambitious and complex project, and the places where she stumbles reveal its worthiness.

Two Trees Make a Forest was book #105 for 2020. I’ve also been reading:

103. Peter Ackroyd, London Under: The Secret History Beneath the Streets

104. Charlotte McConaghy, The Last Migration

What I’ve been reading online

Braiding Sweetgrass is a beautiful book I’m planning to write about here soon. Here’s Robin Wall Kimmerer’s new introduction to it.

Why do young people love nature? Because it doesn’t judge them.

There were once twin elm trees in Preston Park, in Brighton where I grew up. Now there’s only one - but it’s magnificent:

Living near nature can help you kick smoking.

I haven’t watched My Octopus Teacher yet - should I? This story says yes.

This seems like a book that’s very much up my street - Ben Ehrenreich’s Desert Notebooks.

Thanks again for reading! Feel free to hit reply to this email to have a chat (I always write back!), press the heart button if you liked this, or comment.

Also! Follow me on Instagram @hannahjameswords, on Twitter @hannahjamesword and check out my website at hannahjameswords.com.