Raising our voices

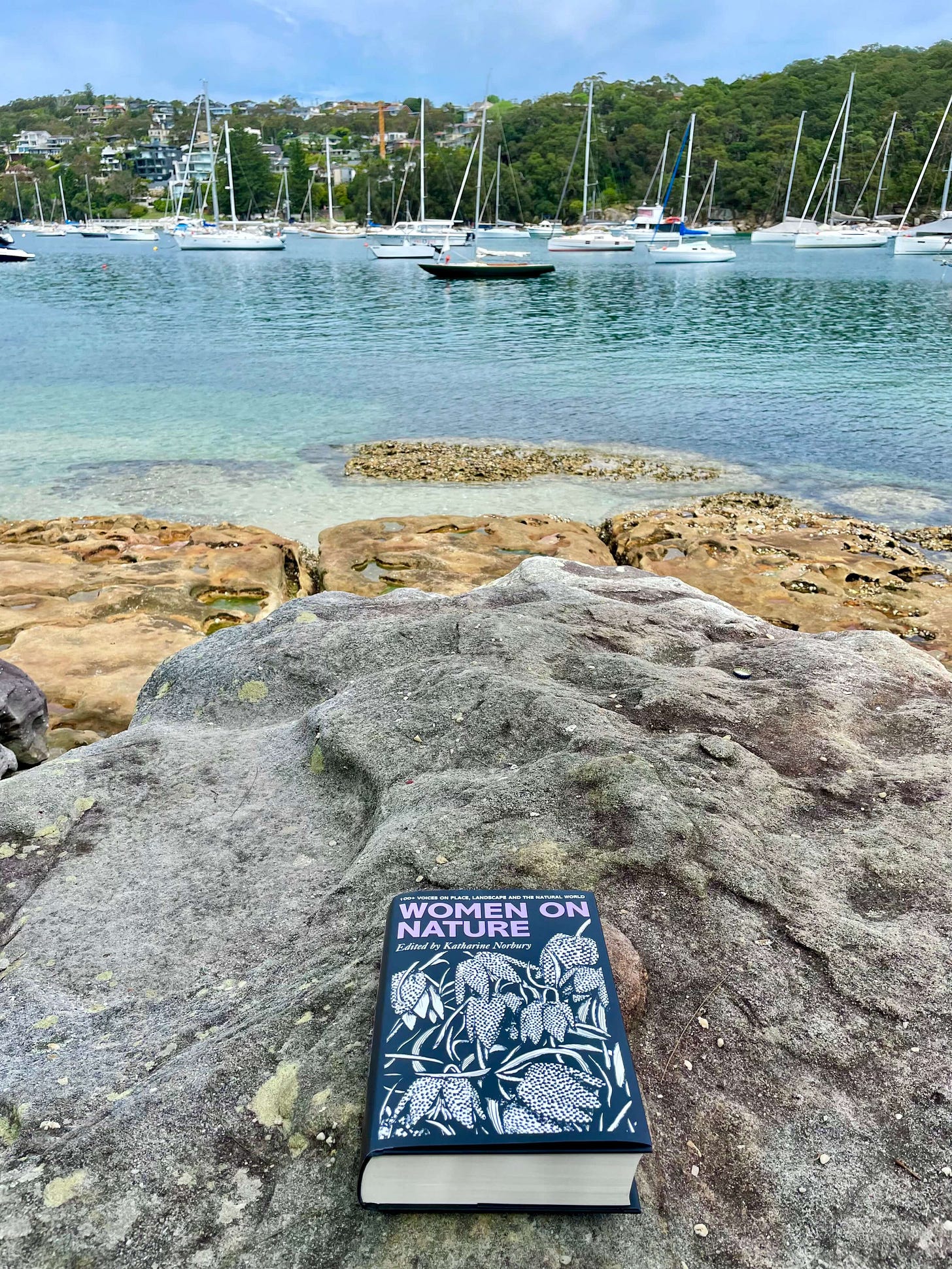

What happens when lone enraptured males are banished and women speak up about nature? I'm reading Katharine Norbury's Women on Nature.

Hi! I’m Hannah James, journalist, writer and editor, and this is where I review nature books, and think about nature-related topics out loud. Thanks for reading!

This newsletter has a new name: The Wild Library. Otherwise it’s still just the same!

Good news: the world’s oldest living rainforest has been returned to its traditional owners.

More good news: James Rebanks’s English Pastoral won the Wainwright Prize. If you’re looking to build a wild library of your own (albeit a UK-focused one), start with the Wainwright Prize longlists. The prize has been running since 2014 and always highlights wonderful work. I wrote about English Pastoral here.

What I’m reading

Scottish poet Kathleen Jamie once wrote that nature writing was dominated by “the lone enraptured male”. She was referring to Robert Macfarlane, who may be lone and enraptured (and is definitely male) but writes superbly about it, so it’s easy to bristle at that description. But her point is powerful: for a very long time, the voices of women in the wild have gone unheard.

These are exciting times for marginalised voices, though. The Nan Shepherd Prize is actively seeking to reward and publish nature writers who feel under-represented, and not one but two female nature writers have recently edited anthologies focusing specifically on other women nature writers.

I wrote about reading Kathryn Aalto’s Writing Wild: Women Poets, Ramblers and Mavericks who Shape How we See the Natural World here. And now I’ve got to the second anthology, Women in Nature, edited by Katharine Norbury, who wrote the wonderful The Fish Ladder.

Like Aalto, Norbury’s project is very specifically to foreground the voices of women, as she writes in her introduction:

“What would happen, I wondered, if I simply missed out the 50 per cent of the population whose voices have been credited with shaping this particular cultural for,? If I coppiced the woodland and allowed the light to shine down to the forest floor and illuminate countless saplings now that a gap has opened in the canopy?”

What happens is precisely what I hoped: a blooming wildflower meadow of glorious and beautiful variety, in which each blossom complements the next. From famous authors of the past (Dorothy Wordsworth; Jane Austen; a brace of Brontes) to current nature writers of note (Amy Liptrot; Kerri ni Dochartaigh; Jini Reddy; my beloved Jay Griffiths) to other names you might not know (poets; biographers; private letter-writers) or might not associate with nature writing (Virginia Woolf; Julian of Norwich), this book is an overflowing cornucopia.

Arranged alphabetically rather than in the more usual chronological order, the book creates lovely conversations between writers vastly separated in space and time. Poet and novelist Natasha Carthew, who founded the Working Class Writers Nature Writing Prize in 2020, nods to the aristocratic 17th-century philosopher-poet Lady Margaret Cavendish. Eighteenth-century poet Charlotte Smith sits between the current novelist Ali Smith and 20th-century poet Stevie Smith. Edith Holden, who wrote The Country Diary of an Edwardian Lady in 1906, gazes curiously at artist and environmental activist Katie Holten’s passionate and beautiful Irish Tree Alphabet (2020). It’s a delicious jolt out of the accepted tenets of “nature writing”, a gentle reminder that women have been thinking and writing about the natural world for as long as there have been women and writing and nature.

On these fronts and many others, this anthology is a glorious success.

A note on work

Working from home during a lockdown is a queasy mixture of monotony and plunging emotional highs and lows. I had to just stop one afternoon last week - my body simply refused to keep going. And I actually like my job!

The role of work in our lives is something we’ve all been mulling over the past 19 months, I imagine. The newspapers certainly have.

The New York Times reported on the ‘lying flat’ trend recently, where workers simply quit their jobs. The ABC predicts ‘the Great Resignation’ will hit Australia in March 2022.

The Evening Standard wonders if the pandemic killed ambition.

The Guardian asked notable writers, musicians and comedians what success means to them now - and for most, it no longer involves the traditional markers of awards and red carpets and fame and acclaim.

New York Times and Buzzfeed journo Charlie Warzel asked, What If People Don’t Want ‘A Career’? (Only he put the punctuation inside the end quote mark, which, like so many things, is The American Way and is also wrong.) He and his partner Anne Helen Petersen, whose Culture Study newsletter I read religiously, have a book out soon about work that promises to be excellent. Petersen’s book Can’t Even, which was kicked off by her Buzzfeed essay on millennial burnout that went super-duper-ultra viral in 2019, is also on my reading list and arguably launched this whole anti-work, anti-hustle culture movement.

What can I add to all these wonderful investigations? Unsurprisingly, very little. Except that I suspect it’s connected to our culture’s increased focus on nature because of the climate crisis. I think (I hope) that many of us are rethinking the capitalist ethos of endless productivity leading to endless growth, because we can see that the rest of the world simply doesn’t work that way. Why would people? Why would economies?

My only concrete suggestion for anyone experiencing their own Great Resignation is also connected to nature. It’s something you have definitely heard before. It’s so obvious, it’s cliched. It’s probably a little naive, and it’s certainly a little embarrassing. But it is simply this: get outside.

I have never felt worse after seeing the wild green world, even if I haven’t felt appreciably better. And usually, honestly, I do feel appreciably better. Maybe it doesn’t last long, and maybe it doesn’t mean much, but it’s better than before. I’ll take it.

A note on failing

There’s a bit of a cult of fake failure at the moment. Turn around and you’ll trip over a podcast or article asking notable people what their failures taught them. But although there’s often wisdom to be found here, it’s coming, inevitably, from famous people viewing their past failures through the lens of current success. Meanwhile, the rest of us are still mired in our own dreary little disasters with no Hollywood movie deal or blockbusting bestseller to reassure us that we still have worth, after all.

If the topic of failure is a little raw for you, as it often is for me at this peculiar moment of midlife, I recommend this lovely essay by Danielle Lazarin, a novelist whose current manuscript is currently on submission to publishers. Its receiving rejections, and her view from the middle of this process is important because it can’t yet be boxed up and labelled as Failure or Success, with all the value and meaning those labels entail. In this awkward edgeland, Lazarin still finds wisdom and comfort - even without a happy ending.

Women on Nature was book number 77 for 2021. I’ve also been reading:

Virginia Woolf, Flush

Wendy Holden, The Duchess

AS Byatt, Possession

Alexander Chee, How to Write an Autobiographical Novel

Paul Wood, London is a Forest

Thanks again for reading! Feel free to hit reply to this email to have a chat (I always write back!), press the heart button if you liked this, or comment.

Also! Follow me on Instagram @hannahjameswords, on Twitter @hannahjamesword and check out my website at hannahjameswords.com.