Oh man, I got no news - you?

Thankfully the Smithsonian does - even if it’s news from the 19th century. Which is, frankly, my favourite kind of news. It’s about the guy who invented hiking. Considering the number of books I’ve read about walking, I would have thought one of them would have mentioned Claude-François Denecourt, who created the world’s first hiking trails in the French forest of Fontainebleau. But none of them did, so thank goodness for the Smithsonian Magazine’s article about him!

And Outside magazine has done an impressive pivot, given that its entire subject matter has been rather sidelined right now, with this beautiful story by Heather Hansman about the pandemic affording us an opportunity to get to know the nature in our neighbourhood. It reminded me of Jenny Odell’s idea in How to Do Nothing about getting to know your bioregion, which I talked about here. (Actually, that bioregion bit forms quite a small part of her book, but it’s obviously made an impression on me!)

Meet the world’s coolest family - they just hiked the whole of the 3000km Te Araroa track, which runs the length of New Zealand, in one go. NZ Geographic is such a great mag!

What I’ve been reading

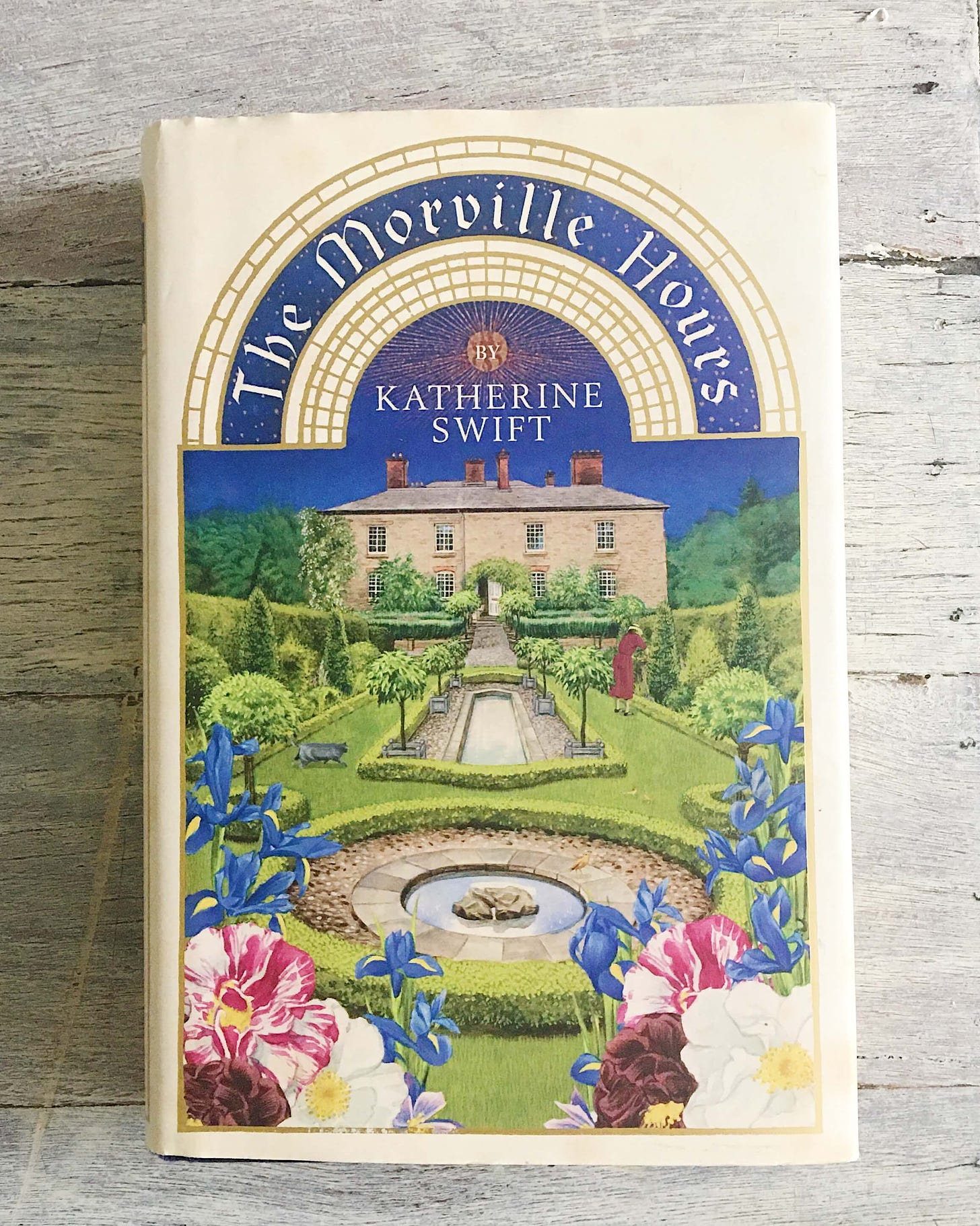

Or rather, re-reading. According to my pencilled note on the inside cover, I bought The Morville Hours, by Katherine Swift, in 2010 while visiting Knole, a stately home in Kent that was the ancestral home of Virginia Woolf’s lover Vita Sackville-West. Woolf described it beautifully in Orlando, her extended love letter to Vita and one of my favourite books. So I’ve owned The Morville Hours for a decade, and judging by all my scribbled notes and underlinings in different pens and pencils, I’ve reread it many times. And I’ll keep reading it, because it’s got SO much in it. (Swift has also written The Morville Year, a collection of her gardening columns for The Times, and - hurray - there’s a new book on the way called Rose for Morville. Can’t wait!)

On one level, it’s the story of how Katherine Swift, an academic and garden historian, created the garden at the Dower House in Morville, Shropshire, where she lives as a tenant of the National Trust. The book is structured in the form of a year in the garden, beginning as the year turns - midnight on New Year’s Eve. In the 12th century, a monastery was built at Morville (later destroyed in the Reformation), and Swift’s chapters are each named for one of the eight church services, the Hours, that formed the waypoints of a Benedictine monk’s day. So The Morville Hours is itself, in its own way, a Book of Hours, those illuminated mediaeval manuscripts that set out the prayers said at each service. Layered within this double structure - a year and the Hours - are too many elements to list. One of its big themes is time, of course, in all its looping, recursive forms. The illustrations in a Book of Hours acted as a precursor to the almanac, describing the seasonal activities that marked out the life of a medieval British peasant, whose history Swift describes. “The 21st century is fighting a losing battle to keep its calendar,” Swift points out. “Gardeners of course have never lost it.”

Onto this framework, she layers the various histories of Morville - geological, social, climatic, political - as well as meditations on the senses, glimpses of memoir, and expositions on subjects as wide-ranging as hedge-laying, the burning qualities of various woods, the history of high days and holy days, and much more. It’s the hedge-laying that gave me a metaphor for the structure of the book: “With its rhythm of bright freshly cut vertical stakes hammered in at intervals, its long swathes of laid boughs, and its trills and top-notes of twisted hazel, it looks like a line of music…” The book took Swift years to write, and her love and labour in working and reworking the text over, just as she works the soil of her garden year after year, are evident all the way through, from the complex, braided structure to the sentences in which each word is carefully chosen and polished bright.

Rosemary and rue, hawthorn and rose and yew, marsh marigolds and meadowsweet, wild violets and pinks and thrift: the book is fragrant with all the sweet old English plants I love. Maybe I’m fragile right now (who isn’t?) but I was on the edge of tears several times during this re-reading, homesick for an England I’m not sure I ever really knew.

Like all great books, The Morville Hours is both timeless and relevant to our era. This quote struck me this time round: “I’m digging in. I travel in time now rather than space, my expeditions only as far as the end of the garden. Distance has nothing to do with remoteness. I am obsessed by roads, but never go anywhere. I pore over maps, but am rooted to the spot. I dream of distant islands, but found one here, bounded by my own garden wall.”

Pandemic reading list, continued

I’m going full escapism here, with children’s books. And if you want to escape the present, I got you: these are all time travel novels (a theme is emerging for this newsletter - and isn’t time doing weird things now we’re all at home, all the time?). I loved A Traveller in Time by Alison Uttley so much that my battered childhood copy - now lost - was missing its cover. Perhaps better known is Tom’s Midnight Garden, by Philippa Pearce. Intended for children a little younger, but still enchanting for adults, is the Children of Green Knowe series, by L. M. Boston. And Five Children and It, by E. Nesbit, is a stone-cold classic.

Oh and I just realised I do have news, although it’s bounded by my own garden wall, like Katherine Swift’s: some of my cosmos seeds have germinated! No luck with the snapdragons yet but it’s only been a week since I planted them. Baby gardener doing well…

See you in two weeks!