Welcoming the light back

A big birthday, winter solstice celebrations and a review of You Call It Desert - We Used to Live There

Hi! I’m Hannah James, journalist, writer and editor, and this is where I review nature books, and think about nature-related topics out loud. Thanks for reading!

Today is my birthday and it’s a big one (OK, it’s 40. I’m 40. Wow). It made me think about time, and seasons, and renewal, and my ongoing quest to find ways to be closer to nature. So I decided to celebrate the winter solstice that precedes my birthday. I wasn’t sure how, so I did some research. Turns out there are plenty of winter solstice traditions around the world that celebrate the return of the sun and the accompanying theme of rebirth, from the Incas’ nine-day festival in Peru (a custom revived in 1944), to the English gathering at Stonehenge to watch the sun rise over the stones after the longest night of the year. And Australia has its own version of Stonehenge: the 11,000-year-old Wurdi Youang in Victoria, an arrangement of stones created by the Wathaurong people that marks the solstices and equinoxes - so perhaps they celebrated solstice, too.

In modern Australia, solstice celebrations mainly seem to revolve around skinny-dipping in icy oceans, but given my cold-water cowardice and the fact that the harbour paths round here are always teeming with joggers, I opted instead to watch the sunrise from a headland. It was lovely and tranquil and surprisingly beautiful, given it was pouring with rain.

What I’ve been reading

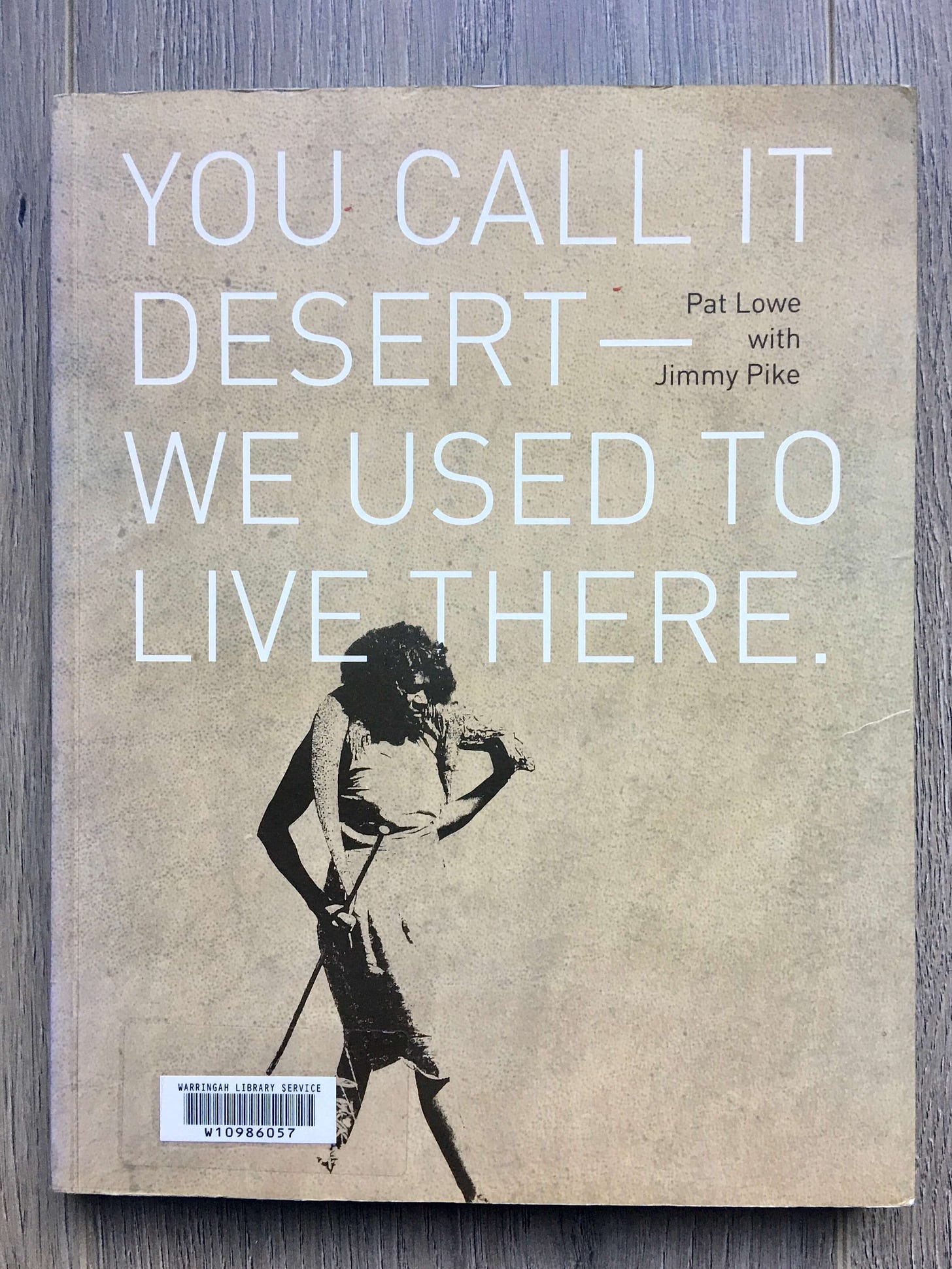

Born around 1940, Jimmy Pike was among the Indigenous people who emigrated from Australia’s central deserts to the Kimberley cattle country in the mid-twentieth century. A Walmajarri man, he walked out of the desert aged seven or eight, having led an entirely traditional life, and became a high-profile artist who exhibited internationally. He also co-wrote books about his culture with his partner, psychologist Pat Lowe, the first of which is You Call It Desert - We Used to Live There (first published in 1990 as Jilji: Life in the Great Sandy Desert). It was written in a camp on the edge of the Great Sandy Desert where the pair lived for three years, and where Pike (who died in 2002) taught Lowe some of what he knew about life in the desert.

The book is illustrated by Pike’s artwork and Lowe’s photos, and is an extraordinary record of how people thrived in what seems to me, frail English rose that I am, an extremely hostile environment. As the title indicates, it’s a profound perspective shift and such a necessary one (I’m reminded of the story of the starving, thirsty explorers in the desert who run into a group of Indigenous people. The locals take pity on the hapless explorers and feed them a feast, all the while puzzling over why the stubbornly ignorant Europeans refuse to take advantage of the desert’s bounty).

It’s full of resonant Walmajarri words - I’m particularly fond of turtujarti, the desert walnut tree - that speak to the close attention the people paid to the natural world around them. The knowledge necessary for survival is embedded in their very language, and so minutely observed differences between types of waterhole each have their own name, as do the varying hills and hollows of the country (which provide shelter) and the progressive stages of grassland regeneration after fire (for food). Wayfinding in the desert is a crucial skill, and so Walmajarri uses cardinal directions constantly in everyday speech, ensuring people grow up always knowing where they are and how to get back to camp. There are chapters on food and medicine and fire and even on children’s games, which give a really rounded, immersive view of a culture whose people were inextricably entwined in nature.

And the book isn’t just a goldmine of fascinating information; it’s beautifully written, too. It’s most lovely where it’s most poignant, when Lowe is describing why the Walmajarri walked out of the desert in the ’50s and ’60s (and even into the ’80s). When relatives working on cattle stations came back over the Christmas holidays, she writes:

“The visitors to the desert never stayed. After a season or two travelling with their relations around their country’s waterholes they were ready to return to the station, where they knew the future lay. And each time a party left, a few more people would go with it. And so, gradually, the sandhills lost their people.”

And they need their people. Whenever the Walmajarri return to the desert to visit, they notice the animals have vanished, the waterholes have silted up, and vegetation has grown over the once-familiar landmarks. Though they lived lightly on the land, the people engineered it very effectively to suit them, and their absence has altered it irrevocably.

Lowe doesn’t want her readers to feel too despondent about the lost Walmajarri way of life, however.

“By blending features from both worlds people are finding a balance to suit them between the old life and the new,” she writes.

We can be grateful for that - and for her and Pike’s invaluable evocation of that old life before it disappeared.

This is book #60 for 2020. Other books I’ve read in the past two weeks:

Mark Boyle, The Moneyless Man

Katherine May, The Electricity of Every Living Thing

Andrew Caldecott, Rotherweird

Pat Lowe With Jimmy Pike, You Call It Desert - We Used to Live There

Andrew Caldecott, Wyntertide

Peter Robb, Midnight in Sicily

Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God (re-read)

See you in two weeks!