Hi! I’m Hannah James, journalist, writer and editor, and this is where I review nature books, and think about nature-related topics out loud. Thanks for reading!

What I’m reading

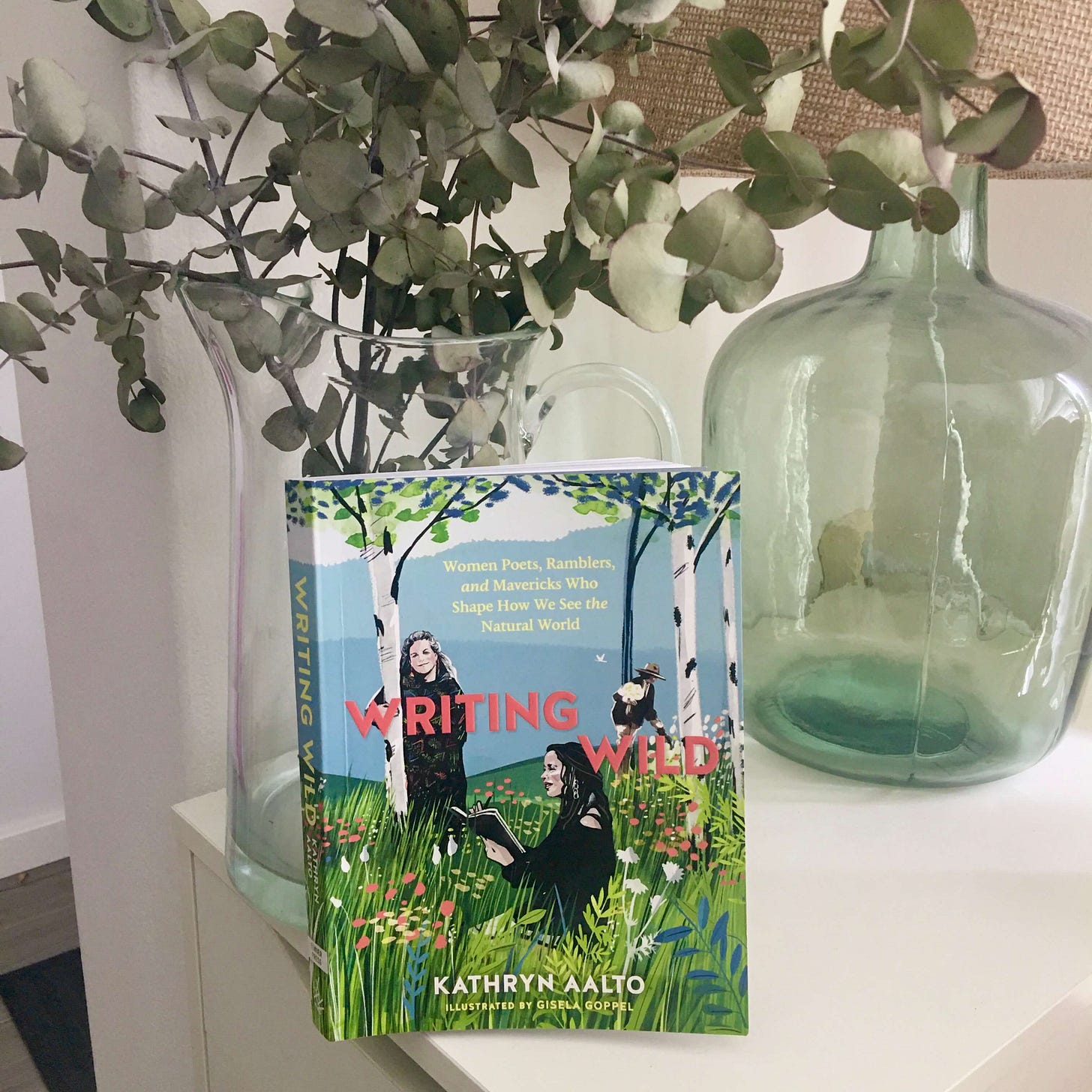

Everyone who loves books loves books about books. From novels about books to bibliomemoirs to literary biographies, writing about reading almost always captivates me. And this week I read a book about nature books - all by female authors. I was always going to love it, frankly.

In Writing Wild: Women Poets, Ramblers, and Mavericks Who Shape How We See the Natural World, Kathryn Aalto collates 25 women nature writers and writes a short essay on each, relating their biographies, quoting them generously, and situating their work within a traditionally male-dominated genre. The book includes writers both well-known (Mary Oliver, Annie Dillard, Helen Macdonald) and less so (Saci Lloyd is a British cli-fi writer; Leslie Marmon Silko is, says Aalto, the first female Native American novelist; Mary Austin was a Californian who wrote The Land of Little Rain in 1903). At the end of each chapter are suggestions for further reading. How I’m going to resist hunting down books with titles like Bedrock: Writers on the Wonders of Geology or As Eve Said to the Serpent: On Landscape, Gender and Art, I do not know.

This delicious compendium was born from outrage: Outside magazine ran a story listing 25 essential books every adventurer should read, and 22 were by men. Aalto furiously wrote a rebuttal, then realised the idea had a book in it. While researching and writing it, she notes,

“I passed through 200 years of women’s history through nature writing.”

Nature writing turns out to be a fascinating prism through which to view not just women’s history, but climate history, too.

“In the two centuries that separate the writings of our first and last writers, a new climate has emerged. The physical world is warmer and less wild. The cultural world is more inclusive and empowering. In this span of time, women have taken ownership of our own narratives by stepping in front of the anonymous moniker ‘By A Lady’ to proudly use our names.”

Dorothy Wordsworth, Aalto’s first writer, for example, never wrote for publication, despite inspiring her more famous brother more than he ever acknowledged. At the turn of the last century, Gene Stratton-Porter benefited greatly from the abbreviation of her given name, Geneva, to a more masculine-sounding version. (She sounds like a blast, by the way: “A gun-toting, bird-loving, moth-chasing, free-spirited film-maker and artist, who opened new territory for women and influenced American environmental ethics.” Yet even her energetic advocacy couldn’t save the Limberlost, 13,000 precious acres of Indiana hardwood forest and wetlands that she wrote about so beautifully, and which were destroyed by Standard Oil. Environmental advocacy is another thread Aalto includes.) It’s inspiring to compare Wordsworth’s quiet journalling with the more recent complex and accomplished science writing of Andrea Wulf, or the soul-baring recovery memoir of Amy Liptrot.

And yes, that does mean Aalto is encompassing a vast range of writing, as she explains:

“I also liberally use the term ‘nature writing’ to include many categories: natural history, environmental philosophy, country life, scientific writing, garden arts, memoirs, and meditations… All these writers are concerned with an essential wildness.”

While all the writers are British or American, they are absolutely not all white. Along with Native American novelist Leslie Marmon Silko, whose 1977 novel Ceremony shows how a World War II veteran with PTSD “slowly reconnects to plants, animals, and his Laguna Pueblo people through ancient rituals to become whole again”, Aalto includes Robin Wall Kimmerer, biologist and author of Braiding Sweetgrass, whose work, as a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, is at the “intersection of science and ancient ways of knowing”. She interviews Lauret Savoy, a geology professor who wrote Trace: Memory, History, Race, and the American Landscape, and whose work is an “inquiry about the intersection of land and identity”. Of Carolyn Finney’s Black Faces, White Spaces: Reimagining the Relationship of African Americans to the Great Outdoors, she says: “A mix of memoir, scholarship, and history, the book traces the environmental legacy of slavery, racial violence, and Jim Crow segregation, while celebrating contributions black Americans have made to the environment.” Poetry isn’t omitted, either: Camille T. Dungy (who edited Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry) writes of nature and motherhood, says Aalto, “intimate moments set to the rhythms of the natural world”.

All this research has led Aalto to make some conclusions about nature writing. First:

“The best nature writing shows close, repeated observations of patterns and rhythms in the natural world.”

This observation has an effect on us human beings:

“The seasonal rhythms of mountains, oceans, skies and deserts help take us out of our depression, anxiety and alienation.”

And finally:

“Classic nature writing [is] a celebration of a particular place and the search for how best to live in the world.”

That’s an excellent summation of why I find nature writing - in all its variety - such a rewarding genre to explore. This book is an excellent addition, not only in itself but also as a signpost to many, many more writers I’m excited to read.

Writing Wild was book #116 for 2020. I’ve also been reading:

I’m planning to read…

Women and nature writing is such a timely combination that there’s another book about them coming out: Women on Nature, edited by Katherine Norbury (author of The Fish Ladder, itself a beautiful work of nature writing), will be out through Unbound in May 2021. This one has a different slant, as it’s a straight anthology of nature writing, rather than short essays about each writer. Which means, unfortunately for my bookshelves, that I’ll have to buy that one, too.

I’m going on holiday

Not literally, sadly, but I’m taking a break from this newsletter for the holidays, and I’ll be back on 15th January. Hope you have a lovely break, feel free to ping any good book recommendations my way, and I’ll see you in 2021!

Thanks again for reading! Feel free to hit reply to this email to have a chat (I always write back!), press the heart button if you liked this, or comment.

Also! Follow me on Instagram @hannahjameswords, on Twitter @hannahjamesword and check out my website at hannahjameswords.com.