Hi! I’m Hannah James, journalist, writer and editor, and this is where I review nature books, and think about nature-related topics out loud. Thanks for reading!

News

This week I was excited to see that British Vogue has developed a love of nature. Editor Edward Enninful commissioned 14 covers for its Reset-themed August issue, snapped by photogs as illustrious as Mert Alas, Tim Walker and Nick Knight, and celebrating nature’s all-too-brief resurgence during lockdown.

And the new issue is accompanied by a new cover challenge. Last month, the magazine’s Black Lives Matter challenge asked BIPOC readers to snap themselves as Vogue cover stars, with results that often truly looked cover-worthy and gave pause for thought about their previous exclusion. For the August challenge, nature is the cover star, with Enninful requesting readers to submit their own pictures of landscapes framed as cover shots.

There’s nothing new about beautiful landscapes photographed as a backdrop to gorgeous gowns, but as far as I remember, fashion magazines have never heroed nature in this way. I’m not sure how many people buy UK Vogue in print, but judging from its Instagram following (4.2 million people), plenty of people still look to it as a cultural barometer, and its cover is still an event, in mag-land and beyond. So this feels significant: a marker that more and more people are finding beauty and solace in nature, which hopefully means more and more people will be motivated to help conserve it.

This is one of the many reasons Enninful is seeming like an excellent choice of editor after Alexandra Shulman’s 25-year tenure. I’ve been so impressed by how he’s risen to the challenge of COVID, as well as positioning Vogue as an active partner in the Black Lives Matter movement.

So what does his new focus on nature mean? If you were feeling cynical, you could construe it simply as a way to capitalise on the enormous popularity of nature images on Instagram - but for me, it’s a good editor doing what good editors do: reflecting and amplifying the concerns of his readers through the lens of the magazine. I’ll be interested to see how people respond to this prompt - what a way to take the temperature of our attitudes to nature!

Connecting with nature

If you don’t already know the nature connection charity Remember the Wild, it’s worth browsing their website and signing up for their newsletter. This edition has lots of great ideas about how to connect with nature.

My own connections with nature this past two weeks have involved whale-watching from the lookout at Warden Head Lighthouse, in Ulladulla, and feeling true joy thanks to a single cosmos flower emerging from the airy froth of foliage in a pot in my back yard. It’s the first plant I’ve ever grown from seed so it feels like a real triumph.

You can’t get more connected to nature than a multi-day hike, and the Carnarvon Gorge Great Walk is a memorable one. I wrote this story about it for Australian Geographic magazine - and the lovely video Don Fuchs, the photographer, created of our trip is here. We met ecologist Dr Kate Grarock on that trip, and she made her own video of the hike, which is just brilliant. Watch it below and subscribe to Kate’s YouTube channel here - her videos will make you long to get out there yourself.

What I’ve been reading

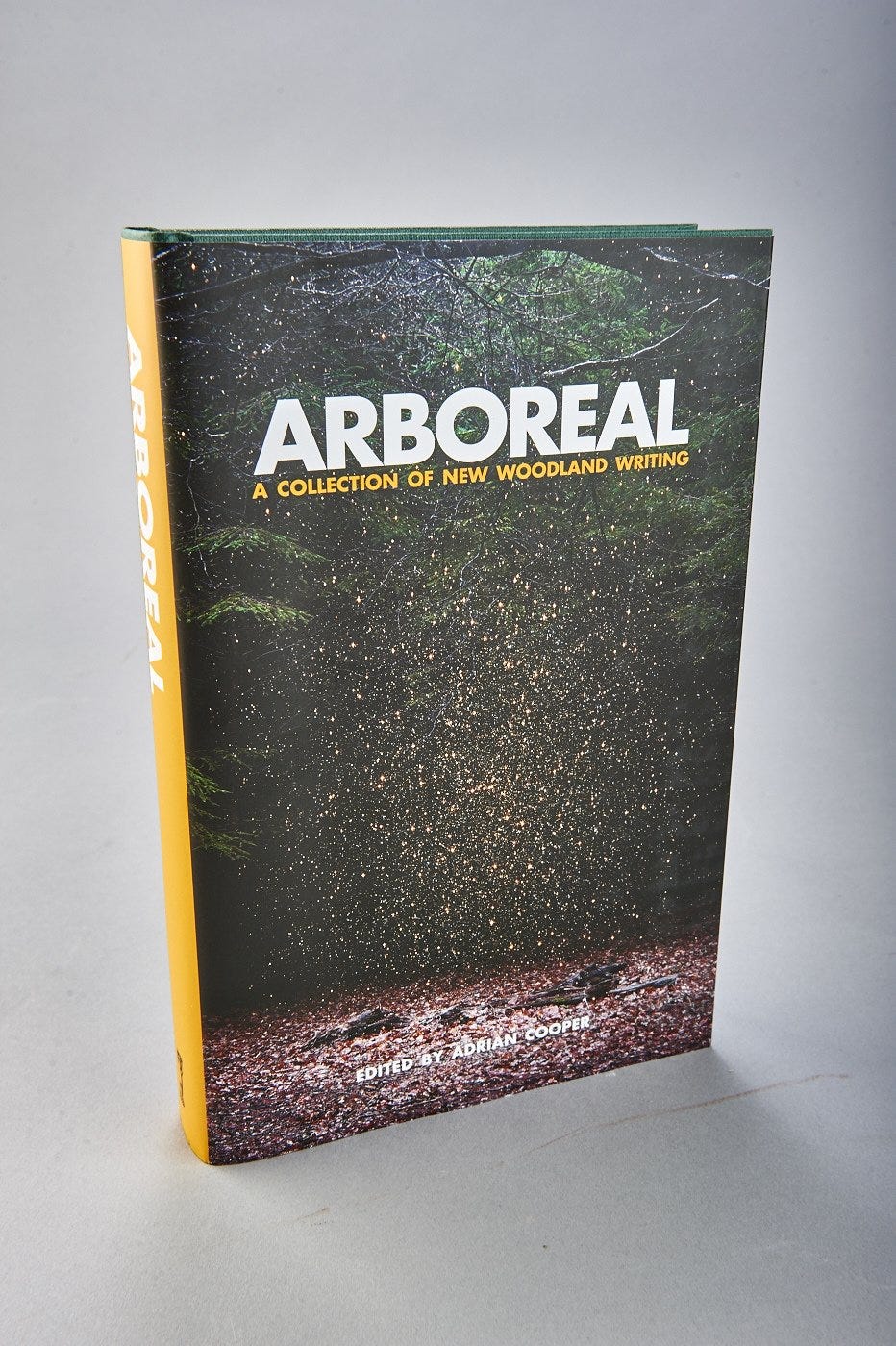

Arboreal: A Collection of Words from the Woods, edited by Adrian Cooper, is an anthology of essays and artworks about woodlands from a variety of voices, including novelists, poets, foresters and architects. It’s wide-ranging in subject, place and tone, as you’d expect, but several themes emerge. Firstly, it’s a tribute to renowned British botanist and writer Oliver Rackham, whose work on the importance of ancient woodlands has had a profound effect on many people. “Ancient” in this case means woods that have been established since 1600 (or even earlier) and, hard as it is to believe, the UK Forestry Commission used to grub up these places to plant serried ranks of spruce and conifers for use in future war efforts. (Well, perhaps it’s not so hard to believe, given that Australian logging companies are still busy destroying ancient ecosystems to produce low-grade wood pulp, even in 2020.)

(Pic borrowed from the publisher Little Toller’s website, as I forgot to take my own photo before I returned the book to the library.)

The mere fact that woodlands can survive for hundreds of years means time is a theme that echoes through the book. Philip Marsden says:

“Woodlands are a dynamic system, but one whose pace of change should be measured in centuries. Like landscape, they are in a state of constant flux – advance and retreat, advance, retreat – but much too slow for our own impatient vision to comprehend.”

Artist David Nash explains how he created Ash Dome, a circle of ash trees in a Welsh wood bound together at their tops to form a dome, in 1977, knowing it would be decades before his vision for it was fulfilled. He likens this to Chinese potters laying down clay in pits for their grandchildren, and the British Navy planting oaks during the Napoleonic wars for ships they believed would be built in the 21st century. Those who work with trees must keep an eye to posterity. (Yet that “constant flux” Marsden mentions means posterity is never assured: sadly, Ash Dome is now succumbing to ash dieback.)

Forester Robin Walter agrees that working with trees is an art on a grand time scale. “For me,” he says, “thinning is creating a living structure in four dimensions.” To make decisions about which trees to fell, he must imagine, as Nash did, how the wood will look in 20 or 30 years:

“It is difficult to imagine and sustain complex structures over decades and centuries. It is more a case of setting the parameters and letting natural processes take over.”

The lifespan of trees, so much longer than our own, means a romance attaches to the oldest of them, some of whom gain names and legends, occupying a deep-rooted place in people’s hearts. Peter Marren explains:

“Ancient trees fill us with awe, and perhaps, in an increasingly godless age, they occupy some of the vacant space in minds once filled with religion. They also help define our sense of place in the world… For anyone and everyone who feels a sense of kinship with them, such great trees are ‘ours’. And, one cannot help wondering, in the unimaginable ways in which a tree interconnects with its environment, are we not also theirs?”

Trees are not only members of our community that can attain a semi-divine status, they’re members of their own “wood-wide web”, via fungal mycelium, an underground network of filaments that connects all parts of the forest to each other, transporting nutrients and communicating information (sometimes about us, as we move through the woods - yes, even as we look at trees, trees are looking back at us).

And as such, trees push back against the idea of themselves as commodities. The concept of ‘natural capital’ is often used as a tactic to persuade governments to treasure and preserve nature, a worthy endeavour - but nature and capitalism are uneasy bedfellows. Philip Hoare despairs:

“Trees, like other plants, have become commodities; an index of capital, rather than celebrated for merely being themselves.”

Yet Robin Walter maintains we can profit from woodlands in a way that doesn’t deplete or destroy them:

“reaping a modest harvest while leaving the wood’s integrity intact… Living off the interest rather than gorging ourselves on the natural capital”.

In fact, working with woodlands may be necessary to their survival, says woodland ecologist George Peterken, who explains that unmanaged woods actually become less diverse. This reminded me of Robin Wall Kimmerer’s beautiful book Braiding Sweetgrass, in which she reminds us that, over millennia, humans have developed reciprocal relationships with the natural world.

This fact hasn’t always been acknowledged, as David Nash explains:

“The environmental movement was split during the 1970s between a belief that the human being is an alien parasite and that nature would be better off without us and a conviction that we are all an essential part of holistic nature, if we can work with it rather than attempting to dominate or conquer it.”

For Paul Kingsnorth - as for most of us, I’d imagine - the holistic attitude is the better option, but we aren’t there yet:

“If there is one thing that the current ecological crisis teaches us it is that we have got our relationships wrong, with the woods as with nature more broadly.”

But if British Vogue can rethink its relationship with nature, I think we all can.

See you in two weeks!

Meantime, do subscribe to this newsletter, hit the heart button if you liked this issue, and share it using the button below. Thanks!

That's a lovely piece, Hannah - thank you! (I'm having a deep flashback to time spent walking across Skye decades ago - such a good place to be that just for that alone you've made my day a good one.)